Losing Weight with Type 2 Diabetes: 3 Reasons People Struggle

Approximately 90% of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese.¹ While obesity often contributes to the development of diabetes, the bigger driver of weight gain is the high insulin levels that are found well before the diagnosis of diabetes.There are some good reasons why the standard advice of “eat less, exercise more” doesn’t deliver results for people living with type 2 diabetes.

Reason #1: With type 2 diabetes, insulin is high, and insulin is a fat-storage hormone²

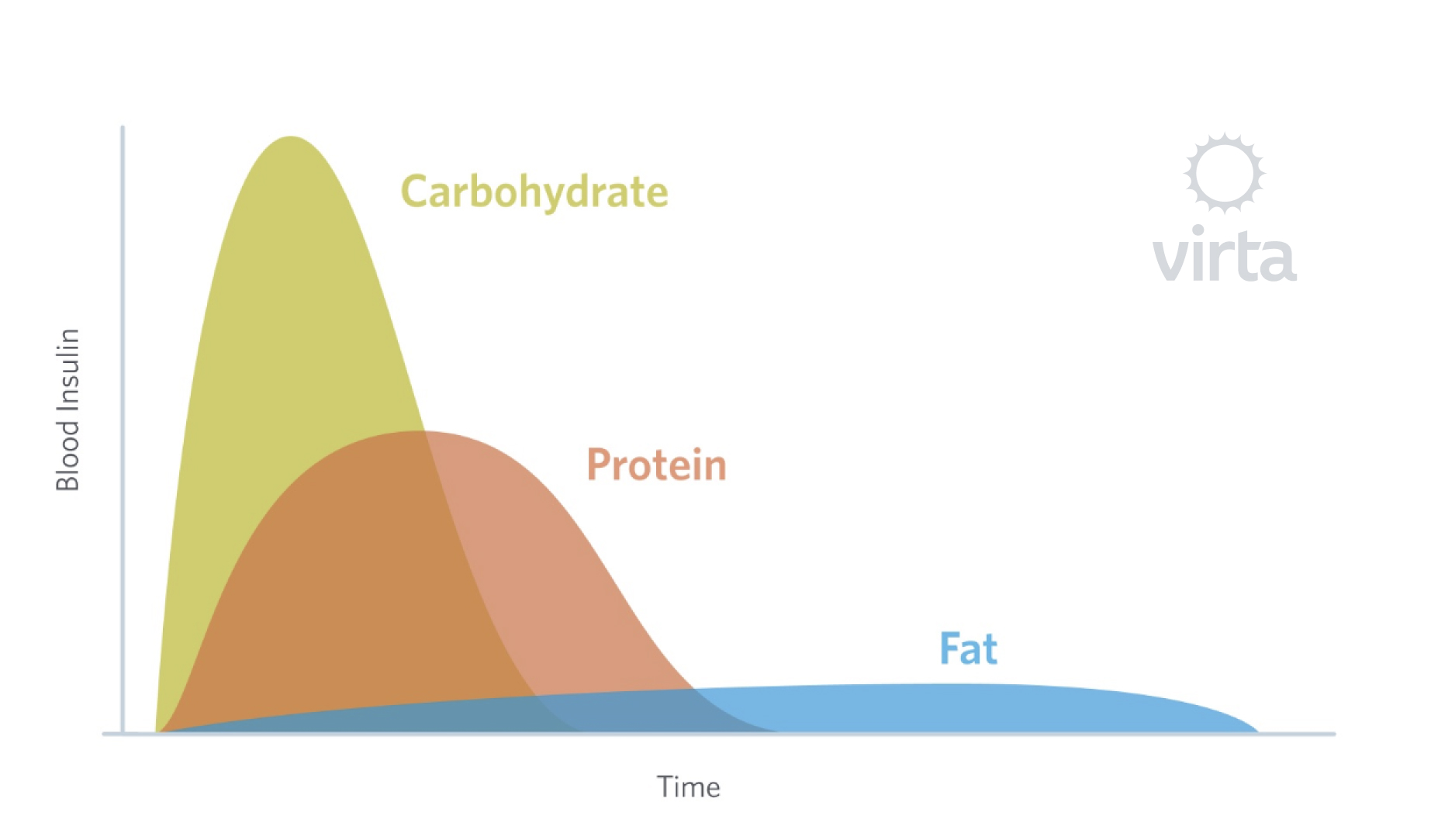

Everyone has glucose, a type of sugar, in their blood at all times. Glucose is a source of energy that largely comes from eating carbohydrates. Simply put, when you eat carbohydrates, your blood sugar rises.

Insulin is produced by your pancreas, and insulin has many functions in the body. One of insulin’s functions is to help get glucose out of the blood and into cells where it can be used. In order to do this, insulin rises along with glucose. So when you eat carbohydrates and glucose rises, the insulin is rising as well. Once in the cells, glucose is mostly used for energy. If you have type 2 diabetes, this process doesn’t work well anymore: your body has become resistant to the signal of insulin, so the insulin isn’t as effective at moving the glucose out of your blood. That’s how you end up with high blood sugar levels after eating carbohydrates. Having chronically elevated blood sugar levels is dangerous, so your body needs to do something about it.

Your body responds by making more and more insulin to try to get the job done. Recall now that insulin has many functions, not just to facilitate the removal of glucose from the blood. Insulin also works to promote the storage of fat and to block the release of fat from fat storage. So instead of losing weight, you just keep gaining, thanks to all that insulin.

Reason #2: Typically recommended eating patterns often backfire by keeping you hungry and keeping your blood sugar high³

If you’re like most people with type 2 diabetes, you’ve been told to eat carbohydrates but eat fewer overall calories, and to eat small meals throughout the day to keep your blood sugar steady; you’ve probably been advised to count your carbs and eat enough of them to keep your blood sugar up after taking medication to lower it—confusing, right?

What many find as a result is that they’re always hungry, always thinking about food and facing cravings. What’s at work is a survival instinct that even the strongest-willed person can’t withstand for long. This is a situation where your physiology is fighting against you. Even worse, those frequent small meals with carbohydrates create spikes in your blood sugar followed by drops in your blood sugar—a blood sugar roller-coaster that stimulates frequent hunger.

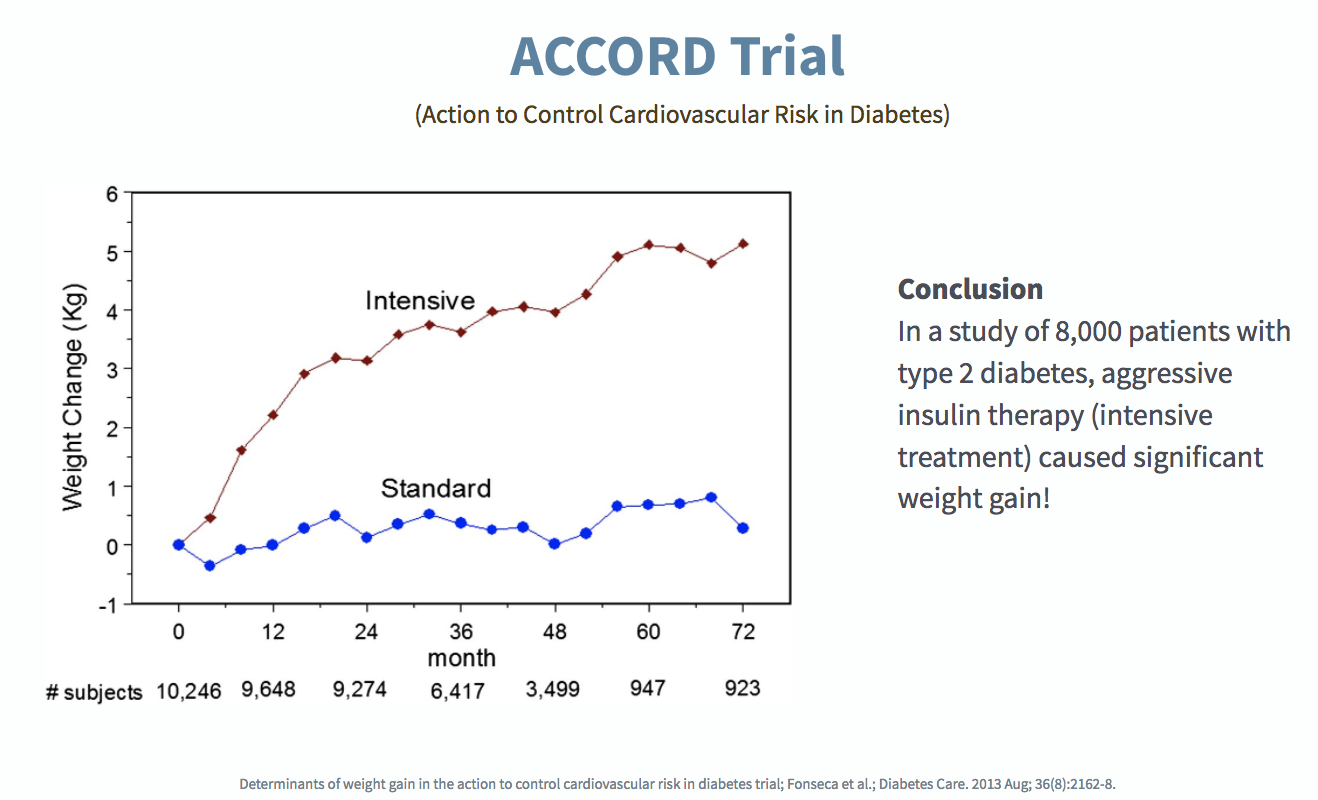

Reason #3: Type 2 diabetes medications can drive weight gain⁴

Remember how your body’s own insulin is a fat-storage hormone? That’s also true for insulin that has been prescribed to you, whether delivered by injection or by pump. That’s why a common side effect of prescribed insulin is weight gain. Another class of medicine for type 2 diabetes, Sulfonylureas, work by stimulating the pancreas to produce more insulin. And once again, more insulin in your body means more fat storage and more weight gain.

What’s the solution?

People living with type 2 diabetes are insulin resistant, meaning their tissues are not responding as they should to insulin. Insulin moves sugar from your blood into your cells. If your body does not respond to its own insulin, then your blood sugar will remain chronically elevated, and your body will produce more insulin. The most direct solution is to decrease the source of high blood sugar itself—carbohydrate consumption.

In fact, insulin resistance can be fundamentally referred to as “carbohydrate intolerance” because when carbohydrates are consumed by someone who is insulin resistant, blood glucose is not lowered as effectively. So, by eating fewer carbohydrates, we both reduce the glucose load in the blood, and decrease the release of insulin.

Nutritional ketosis is a natural metabolic state in which your body adapts to burning fat over carbohydrates as its primary fuel. While carbohydrate consumption triggers spikes in blood sugar, fat consumption does not, making it a better source of fuel for people with insulin resistance.

In a clinical trial, patients lost an average of 12% of their starting body weight within six months by using a medically supervised treatment that included the employment of nutritional ketosis. In addition, 56% of patients with type 2 diabetes reduced their HbA1c to below diabetic levels.⁵

Read more about nutritional ketosis and how it can be an effective diabetes reversal method when paired with physician supervision here.

To learn more about how food affects blood sugar, watch my video series here:

Start on your journey to reverse type 2 diabetes without medications.

This blog is intended for informational purposes only and is not meant to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or any advice relating to your health. View full disclaimer

Are you living with type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or unwanted weight?

- Whitmore C. Type 2 diabetes and obesity in adults. British Journal of Nursing. 2013;19(14):880-886. doi:10.12968/bjon.2010.19.14.49041.

- Wilcox, G. Insulin and Insulin Resistance. Clinical Biochemist Reviews, 2005, 26(2), 19–39.

- Perrigue M, Drewnowski A, Wang C, Neuhouser M. Higher Eating Frequency Does Not Decrease Appetite in Healthy Adults. The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 146, issue 1 (2016), pp: 59-64.

- Fonseca V, McDuffie R, Calles J, et al. Determinants of weight gain in the action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2162- 2168. doi:10.2337/dc12-1391.

- McKenzie AL, Hallberg SJ, Creighton BC, Volk BM, Link TM, Abner MK, Glon RM, McCarter JP, Volek JS, Phinney SD. A Novel Intervention Including Individualized Nutritional Recommendations Reduces Hemoglobin A1c Level, Medication Use, and Weight in Type 2 Diabetes. JMIR Diabetes 2017;2(1):e5. DOI: 10.2196/diabetes.6981